"Ready to jibe?"

“Ready.”

Suddenly, the mainsail, which I had successfully trimmed in for the jibe was headed straight for the water and fast. I had no time to counter the weight of the wind in the sail with my body, being caught off guard at my botched jibe and the weight of my crew on the leeward side. Before I could think twice, I was in the water, swimming around the boat and toward the dagger board. My crew was hanging onto the mast, so as I reached for the dagger board which had not been locked into place, the boat went from a simple capsize to a full turtle. My crew was nowhere to be seen.

As I stood on the edge of the hull, dagger board fully extended now, I shook my head and hoped like hell that my crew could swim. I waited for her to surface, and reflected on how I got myself into this situation.

Earlier in the day, I had rented a Laser 2000 with a novice sailor. It’s not that I am all that experienced myself. I have been sailing for two years, mostly in summer, and I have hopped between Picos (small dinghies) and keel boats. Except for my experience on the Picos and my lessons with the keel, I have not been skipper much. I’m still learning how to identify the wind while sailing, and this is what gets me in trouble.

My rental earlier in the day was to gain experience, and experiment as skipper. After lunch, my English speaking crew from the morning headed off to her prior engagements, and I assumed that I would just be crew for another novice skipper, or I would gain some knowledge from the coach would was helping show us the Laser 2000s.

I was wrong.

As we headed back out toward the boats, one of the novice sailors, the only other woman left in the group, grabbed my arm and insisted that she ride with me. I tried to express that I just wanted to be crew, maybe she could be skipper. I received a very emphatic, “No.” So, there I was, heading back out, a little worse for wear, having woken up at 5:30 that morning to catch a bus.

As we left the safety of the beach, things didn’t seem so bad, except that I was having a hard time catching this wind, which was supposedly right behind us. The wind seemed to be shifting, but it is quite possible that my perception was off from the beginning.

We made it out to bigger water, and we tried some exercises, my crew, whose English was as limited as my Korean, insisted that we fly the jib. I asked her to hold off a bit. I wanted to get my sea legs before adding more power. Finally, her nagging won out, and we were flying the small jib.

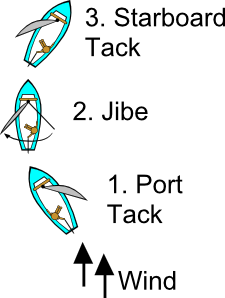

“Ready to tack?”

“Ready.”

Some tacks were better than others, in many I lost speed before the tack for a myriad reasons. Finally, we started working better together. We, being me and the boat, or me and my crew, or all of us all together. I was feeling confident, and I was practicing maneuvering as much as possible. I had to get my sea legs as I was competing in my first ever dinghy regatta the following weekend.

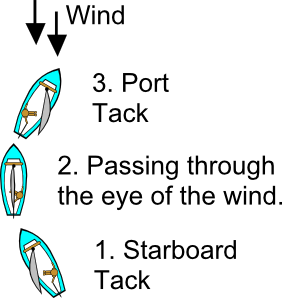

As we sailed downwind, at a broad reach on a port tack, I felt pretty good about our position. The sail was out, we were flying, catching waves and surfing occasionally. Then, I decided it was time

for a jibe.

As I attempted the jibe, something went horribly wrong. We caught a strong gust. The mainsail and my crew headed straight for the water.

I had begun to contemplate the possibility of my crew not surfacing, when I finally saw her. She did not look happy. The first thing she said to me was she was cold. I started immediately insisting that she come help me right the boat. I knew what we had to do, and I knew we could do it. She refused. She would not move from her current position. She shook her head stubbornly, frowned, and held tightly onto the bowsprit.

I started looking around. Standing on the edge of the hull, without it leaning even a bit, I knew it was hopeless for me to attempt this situation alone.

In the distance I saw the jet ski of the marina coming toward us. As it approached, I imagined my crew being lifted away onto the jet ski and carted back to the mainland. The way she was acting, I had started imagining that she was near hypothermia or had been badly injured.

As the jet ski approached, she reached out for it. Hoping to be carted away. Instead, one of the men on the jet ski jumped off and started trying to help my right our boat.

We pushed against the hull with our feet and used the dagger board as leverage. This boat did not want to budge, and it took a long time for us to even get her to a properly capsized position. Finally, we righted the boat, and my first move was to make sure we didn’t capsize again. As she tilted back toward the water, I jumped on the opposite side of the hull and grabbed to uncleat the mainsheet, setting the mainsail free.** I also took the opportunity to furl the jib. As far as I was concerned we would not be needing that bit of power anymore.

I boarded the boat to the best of my ability, but I found that jumping back into a boat after a capsize took the last remaining bit of energy I had. The man who helped right the boat, pulled me in by my life vest.

With my crew being cold and seemingly helpless in the water, as she back-floated over to the rear of the boat, I made the decision to head in. When she insisted that we go back out, I refused.

We headed slowly back in, and I called it a day.

**The cleated mainsail was much of the reason the Laser 2000 was extremely difficult to right as it added additional drag.

Luckily I went out the next weekend with crew I was familiar with. We maneuvered in low, shifting wind and came out sixth place out of eleven teams in the regatta.